‘Kennedy’ Review: Anurag Kashyap’s Convoluted Rogue-Cop Thriller

It’s 11 years since Anurag Kashyap’s electrifying five-hour crime opus “Gangs of Wasseypur” jolted Cannes audiences, triggering renewed global interest in Indian genre cinema and vaulting Kashyap to auteur status with several subsequent films granted A-list festival premiere status — even if none quite matched his breakout feature for ambition or execution. Following a run of lower-profile potboilers in a range of genres that saw him through the pandemic era, Kashyap’s elaborately conceived, brashly violent policier “Kennedy” aims to return him to the art-pulp elite, starting with an obliging premiere slot in Cannes’ Midnight section.

The result is a declarative but somewhat disappointing return to underworld territory. Enlivened by some propulsive action, a hip-hop-inflected song score and a combative streak of anti-institutional protest — in a COVID-era context that proves one of the script’s more interesting specifics — “Kennedy” is ultimately weighed down by hit-or-miss performances and convoluted plotting that isn’t always ahead of its own twists. Internationally, the film is likely too lurid for crossover arthouse interest, though it would be a good fit for major streaming platforms.

It begins, improbably enough, with a Wordsworth quote spread across the screen: “We Poets in our youth begin in gladness; But thereof come in the end despondency and madness.” One might debate how apposite a selection it is, given the film effectively substitutes policemen for poets in the sentiment — either way, any gladness in the title character is largely confined to memory, with despondency and madness having settled in long ago. Uday (Rahul Bhat) is a former cop, believed by most (including his family) to have been killed in action years before, now operating in the shadows as a contract killer who never sleeps and goes by the name of Kennedy. (“You could have chosen Donald Trump,” observes a confidante. “You’d be a certified asshole then.” Kashyap’s political commentary, like his filmmaking, rarely takes the quiet option.)

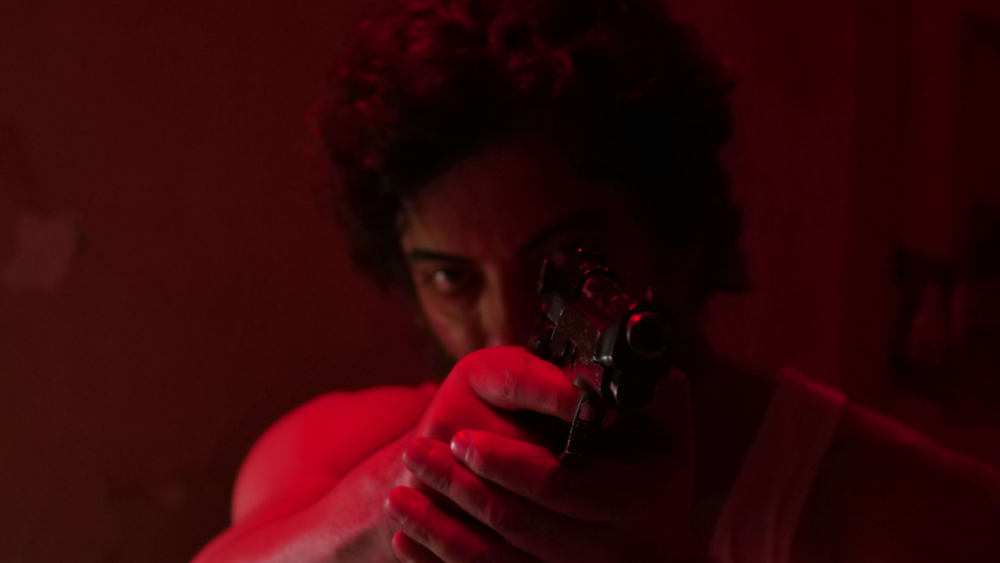

We first see Uday at work as he efficiently slits the throat of a well-off businessman in his luxury apartment, taking one of the victim’s sleek suit coats during the cleanup to replace his own blood-spattered one, before masking up, heading downstairs and slipping behind the wheel of the car he drives for a high-end Uber-style service. We’re in the midst of the global pandemic, with much audible talk about how certain capitalist enterprises and government departments are monetizing the crisis — and so we begin to connect the dots between this social disorder and Uday’s assassination targets.

Some are at the instruction of corrupt police chief Rasheed (Mohit Takalkar), now using his supposedly dead orderly to do his dirty work without trace. But Uday is also working his own revenge angle, exposing a high-places conspiracy that gradually reveals itself as the narrative flashes spottily back and forward across a seven-year timeframe. It takes a few more pivots before we glean exactly how Canadian femme fatale Charlie (an unfortunately stiff Sunny Leone), resident in the same apartment building as Uday’s aforementioned victim, figures into proceedings, or indeed the otherworldly figure who pops up at inopportune moments to give him snide pep talks; the personal backstory that bookends proceedings is rather more obvious.

Amid the film’s narrative clutter, Uday himself never quite comes into focus as a character. Exuding burly, haunted menace, Bhat gives a physically commanding performance in the role, but there’s little sense of transition between insomniac Uday and his Kennedy persona — and Kashyap’s script is too busy keeping its spiraling story in check with clunky explication (“Now I’m asking for help from the man who killed him… do you see the irony?” a character asks at one point) to offer more nuanced assistance.

“Kennedy” is thus best enjoyed on a setpiece-to-setpiece basis, as the director’s genre smarts show themselves best in energized individual action sequences: a pounding chase by foot across the rooftops and walkways of crumbling Mumbai apartments, a joltingly short-tempered sidewalk shootout, a grisly execution with a cast-iron chapatti pan. Though the film’s visual design doesn’t make good on the kitsch comic-noir styling of its opening credits, it’s nonetheless shot with varnished verve by Sylvester Fonseca, while Tanya Chhabria and Deepak Kattar’s agitated editing ensures the film always feels busy, even when it’s sometimes running in place.