Wim Wenders on Why Hirayama, the Tokyo Toilet Cleaner in ‘Perfect Days,’ Matters: ‘There Are No Nobodies!’

“Perfect Days,” which world premiered in Competition at the Cannes Film Festival, is reminiscent – in some ways – of “Groundhog Day,” but whereas in the latter film Bill Murray’s character, Phil, is trying to escape the repetitive nature of his existence, in Wim Wenders’ film the protagonist, Hirayama, is “embracing it,” the German director tells Variety.

Both films show the lead characters waking at the same time each morning, but whereas, in “Groundhog Day,” Phil is awoken by an alarm clock, in Wenders’ film, as he points out, Hirayama, played by Cannes best actor winner Koji Yakusho, “wakes up on his own, or he wakes up because there’s an old lady brushing the street outside, always on time. He doesn’t need an alarm clock. He doesn’t even own one.” There is a sense that this is a man in harmony with nature, and at peace with his existence, rather than wrestling with it.

“When he opens his eyes, he’s happy that this new day starts. And that’s where the similarity with ‘Groundhog Day’ abruptly stops,” Wenders says, seemingly happy to escape the comparison. “He’s not suffering from having to go through his routine.”

“Perfect Days”

Courtesy of MasterMIND Ltd.

Part of the reason for the contrast between the two characters may lie in differences between certain aspects of traditional Eastern philosophy, where the idea of repetition doesn’t necessarily have a negative connotation, and the restlessness of contemporary Western culture, with the aspiration to move onto something new, rather than appreciate what already exists.

In Japanese crafts, pottery for example, there is an emphasis on the nobility of the process, with the repetitive nature of making a pot again and again leading to perfection. Hirayama is, admittedly, no craftsman, he cleans and maintains toilets in Tokyo – which are works of art in themselves – but he nevertheless approaches the task with the same eye for detail, pride and dedication with which a master potter approaches ceramics.

Wenders says: “You know, the potter’s secret is doing it for the first time each time, and for our man, Hirayama, it’s the same. Each day, he’s doing it for the first time. And he’s not thinking how he did it yesterday, and not thinking how he will do it tomorrow. He’s always doing it in the moment. And that’s the potter’s secret as well. And that’s what gives a whole different dignity to any repetition.

“Perfect Days”

Courtesy of MasterMIND Ltd.

“Repetition as such, if you live it as repetition, you become the victim of it. If you manage to live it in the moment, as if you’ve never done it before, it becomes a whole different thing. You’re totally right. Crafts in Japan have a whole different tradition and are still lived in a different way than crafts in our Western culture, in which crafts are disappearing rapidly, dramatically. It’s really a shame. I’ve seen some of the last of their craft, trying to find somebody who was going to take it over, but they couldn’t.”

Just as a craftsman pays attention to every detail, whether people notice or not, it matters to Hirayama that everything is perfect. Wenders says: “Hirayama has made some of his tools himself, for instance a little mirror on a long stick to look underneath the bowl. Nobody else would see if there’s a drying drop there, but he does. Well, it’s not a ‘craft’, he’s not a craftsman, he’s a serviceman, but crafts and service are equally unbearable if it’s always the same. And it becomes a beautiful, dignified job if you reinvent every day what you do and who you do this for. But most of all, you have to like the act of being of service.”

Hirayama notices things that other people don’t, like the homeless guy who’s always standing underneath the same tree. Hirayama has got the kind of vision that maybe some of us have lost, of seeing everybody, or at least not ignoring them.

Wenders says: “The skill is very simple: for him, all people are equal. For him, there are no nobodies. In his own opinion, he is not a nobody either. So, he recognizes the ‘nobodies’ around him very acutely. That homeless character, too, is an important human-being in his eyes. Because Hirayama notices him, we see him, and we see how amazing he is. We wonder what life he had. In Los Angeles, I made a film, ‘Land of Plenty,’ and we shot among the homeless community. And the amount of heartbreaking stories you’d hear… people who were professors, teachers, with academic degrees who were now out on the street. There are no nobodies!”

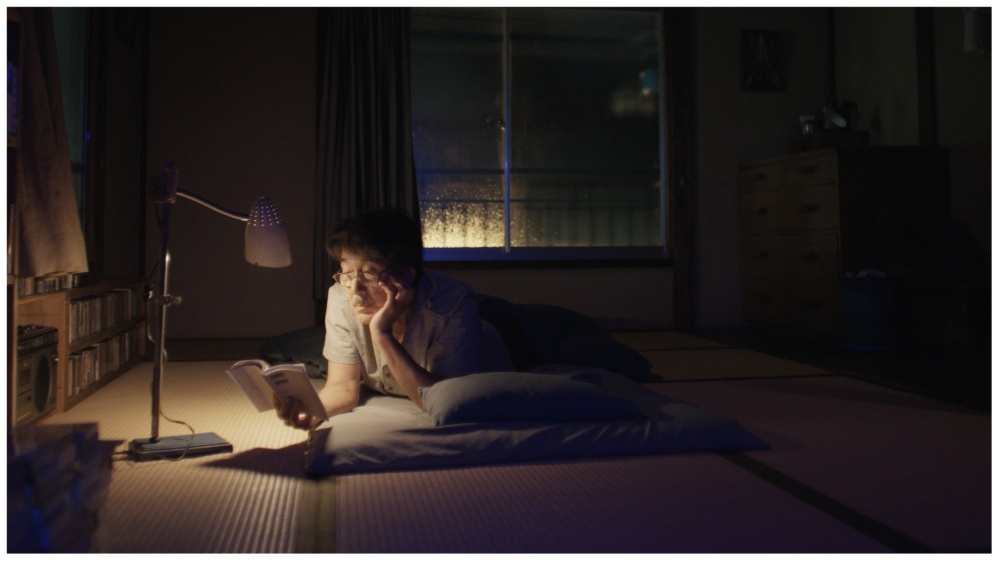

“Perfect Days”

Courtesy of MasterMIND Ltd.

At the start of the film, we know very little about Hirayama, and it is only with the introduction of, first, his niece, and, then, his sister – who is clearly far wealthier than he is – that we get to know a bit more about him.

Wenders says: “We guess a little bit, but even with [the introduction of his sister], we don’t know all that much. We only guess that he must have had a very different past. He probably had a Lexus himself. Maybe he was a successful businessman. And then something happened, so he chose a different life, a more fulfilling, and simpler one. Maybe he needed healing, and now the way he lives is a lesson for us in healing.”

It’s almost like we’re meeting him for the first time, and then by observing him we learn a little more about him, rather than it being fed to us in the script.

“Yes. Exactly,” Wenders responds. “Through entering into Hirayama’s life, we slowly enter into his way of seeing. But very seriously: every film teaches us its own perception. Some films teach us to see carelessly, others show us how to see with a loving look.”

Like many of Wenders’ films, “Perfect Days” has a memorable soundtrack, and takes its name from one of its songs – the Lou Reed classic “Perfect Day.” Hirayama’s favorite tracks are heard as he plays his cassettes in his van or in his apartment, and they give us another way to get to know him. Did the songs come first, with the scenes composed around them?

“Perfect Days”

Courtesy of MasterMIND Ltd.

“Some of the songs were written into the script already, like Nina Simone’s ‘Feeling Good’ at the end. Some of the songs imposed themselves. The choices were important as they defined Hirayama’s taste and who he is. Plus, there’s the fact that he is listening to audio cassettes. He still has his old cassettes from when he was young. He listened to British and American rock music when he was young, but also to Japanese folk and country music of the 70s. So, he still listens to the same cassettes, and he still connects to these emotions.

“And in our story, all of a sudden, he realizes that his cassettes, as outdated as they are, are now suddenly the hottest shit in Japan. I mean, now you find whole shops with nothing but vintage cassettes. Walkmans and cassette players are coming back. And the coolest thing for young people is to make compilations again, analog stuff. Unlike digital “playlists”, you cannot switch the order, but you follow the order of the compilation. Like you read a letter.

“I finally got all my compilation tapes out of the basement where they’ve been for 40 years, and started enjoying them, and even my old Nakamichi cassette recorder still works well. It has Dolby A, B and C. Not that it matters. It sounds different. That old cassette sound might not be hi-fi, but it has power.”